In late 19th-century France, a quiet revolution was taking place in the art world—one that not only changed what artists painted but also transformed how people saw the world.

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism were two closely connected yet fundamentally different movements in Western art. Both emerged in France and, within less than half a century, completely reshaped the trajectory of modern painting.

Impressionism sought to capture what the eye sees—the fleeting effects of light—while Post-Impressionism aimed to express what the mind feels—the artist’s subjective interpretation of the world. Their dialectical relationship laid the foundation for modern art.

01. The Birth and Innovation of Impressionism

The emergence of Impressionism in the 1860s marked a major revolution in art history. It freed painting from its dependence on history, mythology, and religion, and abandoned the traditional narrative style.

Impressionist painters boldly rejected academic conventions, shifting focus from storytelling to pure visual experience.

On April 15, 1874, a group of young artists organized their own exhibition in Paris to challenge the official Salon. Among them were Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, and Berthe Morisot.

The group embraced a mocking label coined by critics: “Impressionists,” derived from Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise, which had been ridiculed during its debut.

Drawing from Realism, they began exploring the effects of outdoor light. Based on new optical theories, Impressionists believed that color was produced by light and that “local color” did not exist.

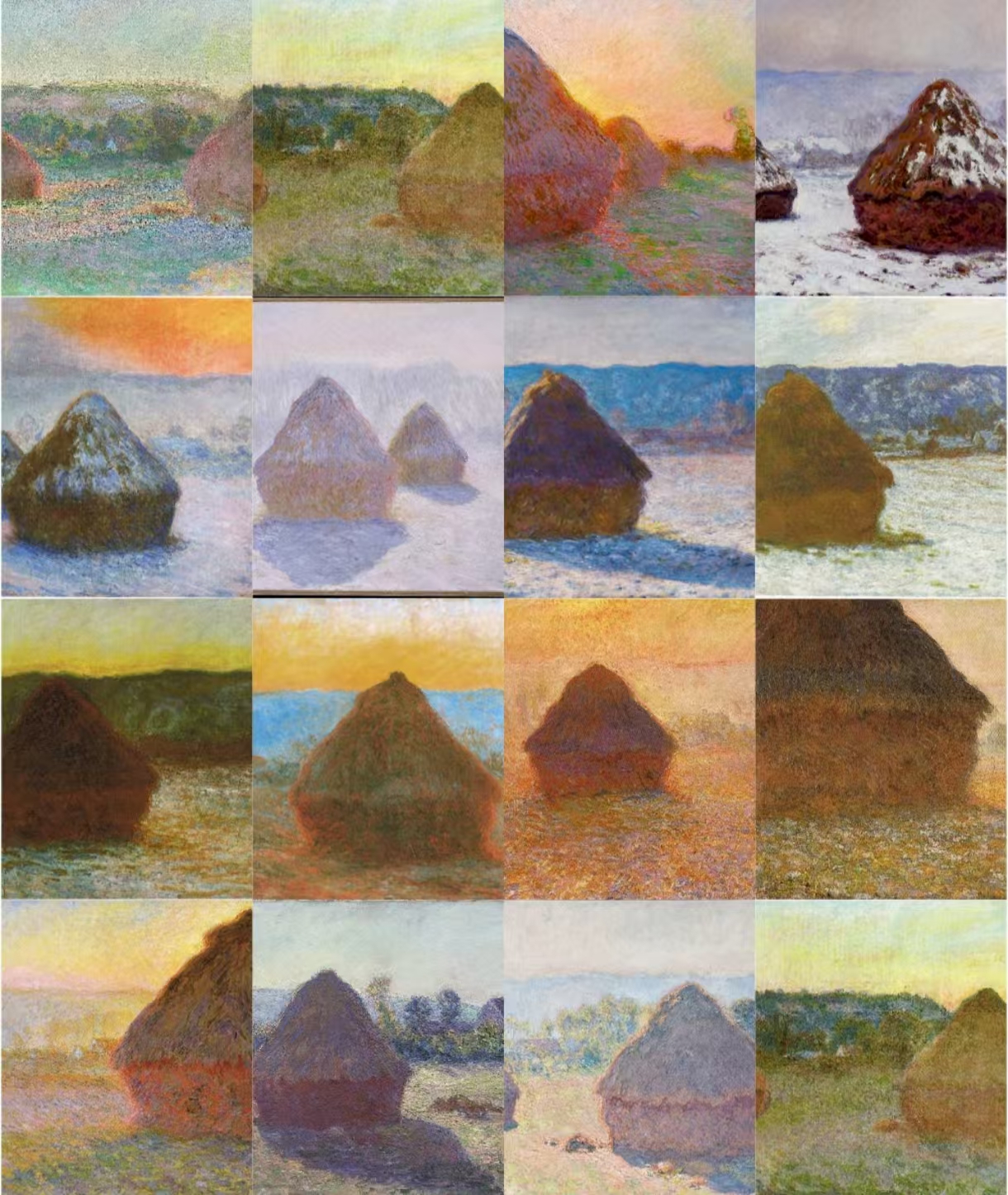

They painted en plein air, depicting sunlight and daily life with broken brushwork and vivid hues, rejecting the brown tones of earlier centuries.

02. The Formation and Rebellion of Post-Impressionism

The term “Post-Impressionism” was coined by British critic Roger Fry in 1910 when organizing a London exhibition of modern French painters.

Post-Impressionists arose from dissatisfaction with Impressionism, believing it focused too much on external appearances and neglected emotional and symbolic depth.

They argued that art should go beyond objective reality and express the inner world. Unlike the Impressionists, they valued emotional resonance over optical accuracy.

Post-Impressionism was not a formal group and had no shared manifesto—each artist developed a distinct style.

They rejected the purely scientific approach to depicting light and color, asserting that the artist’s personal perception mattered most. As Cézanne put it: “Painting from nature is not copying the object; it is realizing one’s sensations.”

03. Fundamental Differences in Artistic Vision

The essential divide between Impressionism and Post-Impressionism lies in how they treat the relationship between the objective world and subjective feeling.

Impressionists sought to reproduce natural reality, capturing transient light and color. Post-Impressionists, in contrast, emphasized form, emotion, and structure over naturalism.

While Impressionism pursued optical realism, Post-Impressionism elevated formalism—reducing nature to geometric order and inner harmony.

Post-Impressionists respected the achievements of Impressionist light and color but focused more on material solidity, structure, and emotional resonance.

04. Key Artists and Their Styles

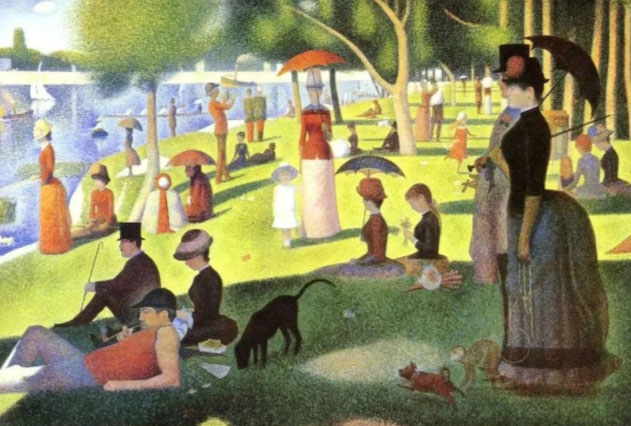

Major Impressionists include Édouard Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Sisley, and Pissarro. Leading Post-Impressionists were Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh.

Cézanne, often called the “Father of Modern Painting,” paved the way for Cubism and Expressionism. He sought harmony through structure, reducing nature to spheres, cones, and cylinders.

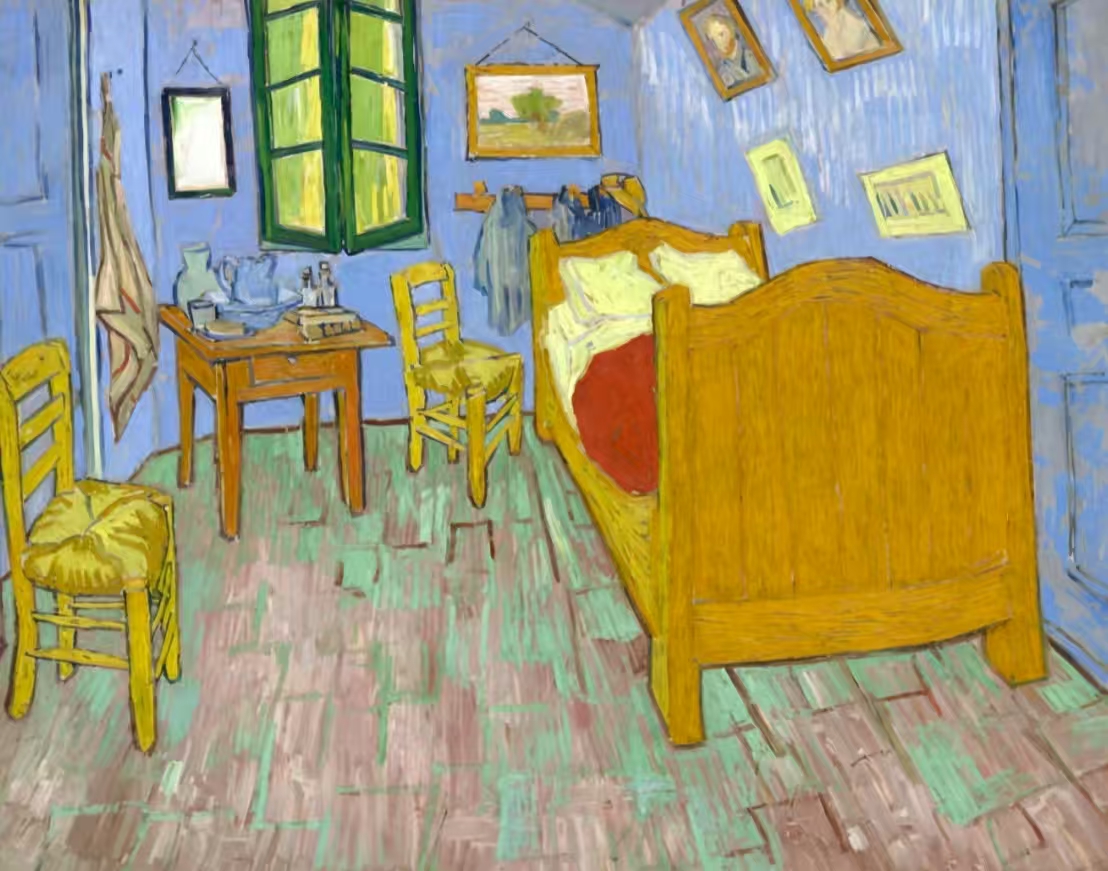

Van Gogh focused on emotional and spiritual expression. As he wrote, “To express what I see, I use color more arbitrarily to express myself forcefully.” His bold use of pure color, seen in Sunflowers, transformed color into a vehicle of emotion.

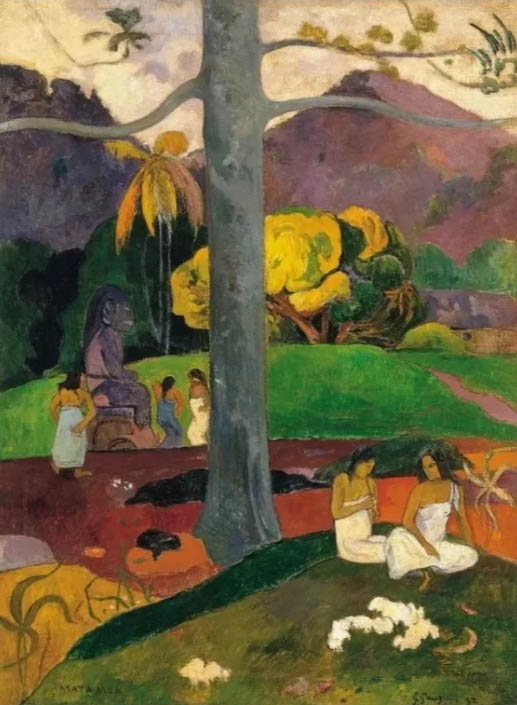

Gauguin emphasized symbolic meaning and spiritual content, using flat, decorative color planes inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and non-Western art to express emotional liberation.

05. Techniques and Methods

Technically, Impressionists used broken brushwork, visible strokes, and unblended colors, provoking both admiration and outrage among their contemporaries.

These methods divided viewers: some saw them as mere tools for traditional aims, while others viewed them as radical innovations.

Post-Impressionist techniques were more diverse. Cézanne ignored perspective and anatomy, building forms through color patches. Others emphasized shape, contour, and composition over realism.

Post-Impressionists believed art should transform the visible world through emotion and structure—turning the “objective” into the “subjective.”

06. Influence on Modern Art

Post-Impressionism broke away from Western traditions of objective representation, inspiring both Abstract art and Expressionism.

It is often regarded as the true beginning of modern art. Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh—sometimes called the “Three Titans of Post-Impressionism”—believed painting should express inner truth rather than reproduce outer light.

Post-Impressionism’s focus on structure, deformation, and emotional expression directly influenced the rise of the Fauves, Expressionists, and Cubists.

07. Reinterpreting Historical Significance

From a broader view, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism represent distinct phases in Western art’s evolution. Impressionism bridged beauty and awkwardness, tradition and rebellion—“the last true art and the first false one,” as some critics said.

Impressionists defied the establishment by rejecting academic constraints, democratizing exhibitions, and opening art to public participation.

Post-Impressionism marked a deeper philosophical turn—shifting art from scientific observation to metaphysical reflection. Modern Western painting would henceforth follow two revolutionary paths: breaking traditional perspective and reimagining color theory.

Impressionism brought painting outdoors, from history and myth to daily life; Post-Impressionism took art inward—from the eye to the mind, from representation to expression.

Together, they completed the shift of art’s focus from the hand to the heart within half a century.

Today, in contemporary museums, the distorted bodies, vibrant colors, and restructured spaces all trace back to those rebellious Parisian painters of the late 19th century. Art has evolved—from a way of knowing the world to a way of feeling it.

About Artphiloso

Hi, I’m Philo, a Chinese artist passionate about blending traditional Asian art with contemporary expressions. Through Artphiloso, my artist website, I share my journey and creations—from figurative painting and figure painting to floral oil painting and painting on landscape. You'll also find ideas for home decorating with paint and more.

FAQs

How did Japanese Ukiyo-e prints influence these movements?

Impressionists borrowed compositional ideas and everyday subjects, while Post-Impressionists—especially Van Gogh and Gauguin—were inspired by bold colors and flat decorative forms.

How did photography affect Impressionism and Post-Impressionism differently?

Photography pushed Impressionists to explore color and light beyond the camera’s reach, while Post-Impressionists abandoned realism entirely to express emotion and abstraction.

How did their working methods differ?

Impressionists painted rapidly outdoors to capture fleeting light; Post-Impressionists worked slowly in studios, refining structure and form—Cézanne, for instance, reworked a single theme for months.

How did Post-Impressionists reinterpret portraiture?

Impressionists blended figures into their environments; Post-Impressionists emphasized symbolism and geometry—Gauguin’s Tahitian women evoke mysticism, while Cézanne’s figures become solid forms.

What impact did they have on the modern art market?

Impressionists pioneered independent exhibitions and direct sales to the middle class; Post-Impressionists shaped the modern art market by valuing individual style and theoretical depth.