The artist we explore today, Caravaggio, embodied a gambler’s audacity and a Dionysian fervor strikingly similar to Francis Bacon, who lived over three centuries later. He represents, in my view, the quintessential artist’s charisma. Born Michelangelo Merisi, he deliberately shed this archangelic name, reinventing himself as "Caravaggio" after his parents’ birthplace.

However, before delving into this Baroque master’s world, we must contextualize a pivotal artistic shift: how the pursuit of "ideal beauty" in the 15th-century Renaissance gradually transformed into the dramatic grandeur and epic sensibility of the 17th-century Baroque. This evolution (c. 1450–1600) was nuanced, unlike the stark stylistic divisions of 19th- and 20th-century modernism. The driving force behind Renaissance-era change lay in artists’ evolving conceptions of "reality" and "beauty."

Understanding Caravaggio hinges on reconciling seemingly contradictory critiques: his "devotion to reality and nature" versus the potent theatricality of his compositions. Why is he deemed a Realist? How can an artist who draped saints in peasant rags be central to the opulent Baroque? Resolving these paradoxes requires defining core concepts—what constituted "reality," "beauty," and the essence of Baroque—within their dynamic historical flow.

Thus, this prologue traces artistic practices from the High Renaissance to Mannerism, examining shifting treatments of reality and beauty to illuminate Caravaggio’s Baroque innovations. This transitional period marks art history’s pivot from classical paradigms toward modernist pluralism—a foundational understanding for appreciating Caravaggio’s genius.

I. The cornerstone of the Renaissance: The Pinnacle of Ideal Beauty

What did the Renaissance "rebirth" revive? Amid 15th-century plague and waning Church authority, the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Constantinople—ending the Roman Empire—galvanized Italians. Rome, once the caput mundi (head of the world), lay diminished. Reclaiming ancient glory manifested as reverence for Greek culture.

The Greek ideal celebrated harmony: physical perfection, intellectual vigor, and moral virtue. Greek sculptures, created for temples, pursued an idealized beauty beyond mere verisimilitude. Plato’s Theory of Forms (Ideas) underpinned this: beyond imperfect sensory objects existed perfect, immutable archetypes. A "chestnut" in the abstract realm is flawlessly round, smooth-tipped, and sweetly textured—unattainable by any real chestnut. Classical art thus sought finite expressions of infinite perfection.

The High Renaissance (c. 1490–1520) achieved unprecedented heights through science-art synergy: Albrecht Dürer’s geometry and perspective studies; Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical dissections (often legally dubious). This granted not just technical mastery (precise perspective, anatomical accuracy) but a cognitive revolution. Understanding subcutaneous muscles, fascia, and bones enabled artists to master light, shadow, and form—rendering complex poses sans models. Anatomy taught not just how to draw, but how to see: truth lay beneath the surface.

Thus, Renaissance masters realized the precision unattainable by Greeks. Studying nature, they repaired its "flaws" through idealized beauty. The "Renaissance triad" (Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael) epitomized this: balanced compositions, harmonic proportions, and dignified poise embodied perfection. Herein arose a critical impasse: once perfection seemed achieved, was art’s path exhausted? Was "perfection" synonymous with "beauty"? Could "imperfect" art claim validity? Mannerism emerged as the answer.

II. Mannerism: Loosening Rules and the Germ of Modernity

Mannerism (c. 1520–1600) bridged the High Renaissance and Baroque. Art historian E.H. Gombrich deemed it "the first modernism." Its name, Maniera, implied both "a new manner of painting" and "in the manner of Michelangelo."

Michelangelo—longest-lived of the triad—pushed boundaries late in his career (e.g., Medici Chapel sculptures). This inspired innovators and legions of imitators, often superficial. Hence Mannerism’s pejorative alias, Manierismo ("affected style"), mocking hollow mimicry.

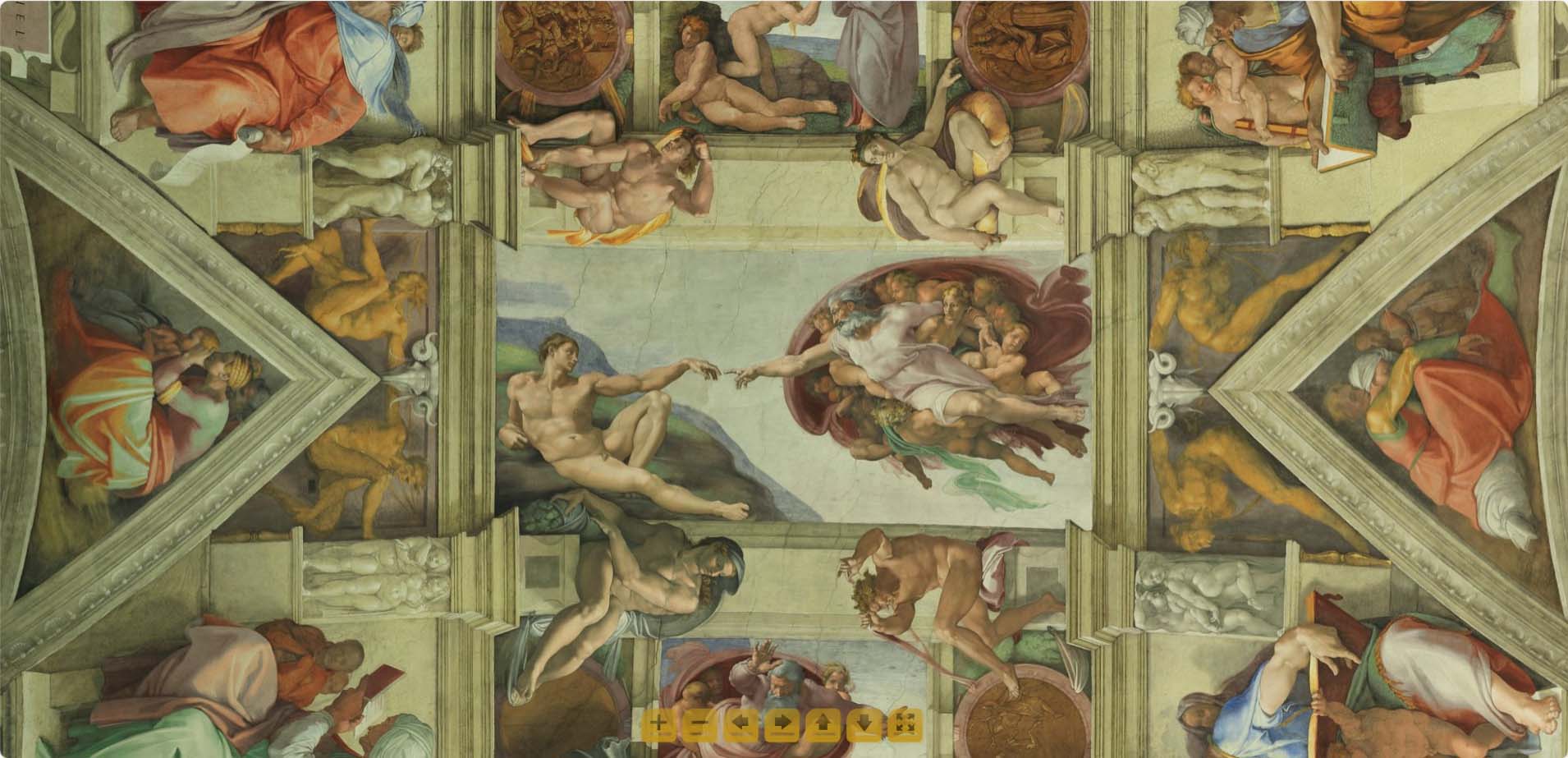

If the Renaissance pursued an idealized reality, Mannerism embraced deliberate distortion. Michelangelo’s late masterpiece The Last Judgment (Sistine Chapel, 1536–41) exemplifies this: elongated limbs, contorted poses, and bulging, rock-like muscles defy classical harmony, evoking awe (terribilità) mirroring the artist’s formidable persona. Compositionally unstable, its figures surge with kinetic energy, abandoning Renaissance serenity for expressive intensity—a legacy visible in modern works like JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure.

Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (1534–40) epitomizes Mannerism. The Virgin’s swan-like neck and the unnaturally stretched Christ Child defy gravity, seemingly sliding along her cascading silks. A gaunt, disproportionately small prophet crams the lower right, violating perspective—foreground and background flatten into disjointed planes, presaging Surrealism. Figures cluster leftward, unbalancing the canvas, while the Madonna’s sumptuous attire and coy allure subvert traditional piety. Where Renaissance masters embodied a quest for truth via craftsmanship, Mannerists acted as rebellious youths, shattering perfection’s rules to explore beauty in imperfection.

III. Toward Baroque: Unleashing Emotion and Foreshadowing Dynamism

Our focus shifts to El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), a late Mannerist active on Baroque’s cusp. This Greek-born painter, working in Spanish Toledo, encountered less rigid criticism away from Italian centers. His emotional intensity resonated locally, necessitating a workshop for commissions.

The Vision of Saint John (The Opening of the Fifth Seal) (1608–14) breaks formally with tradition (elongated forms, subjective color, turbulent composition). More crucially, it reinterprets religious themes with profound humanity and philosophical depth. Unlike early Renaissance icons that suppressed emotion to elevate divinity, El Greco foregrounds raw human feeling.

The painting depicts Revelation 6:9–11: Saint John witnesses souls of martyrs beneath the altar after the Lamb (Christ) opens the Fifth Seal. John’s anguished, upward-straining pose—unscripted in the Bible—is El Greco’s passionate interpretation. The agitated nudes represent martyrs’ souls. Compared to The Last Judgment’s terrifying grandeur, this scene—humans despairing, pleading for divine vengeance—is psychologically harrowing. El Greco’s fusion of visceral emotion, dramatic light, and spiritual urgency heralds Baroque aesthetics—and provides the key to understanding Caravaggio.

Epilogue: The Significance of Transformation and Baroque’s Dawn

We have traversed the Renaissance’s pursuit of ideal beauty, through Mannerism’s rebellious experiments (Parmigianino’s dissonance, El Greco’s emotionality), arriving at Baroque’s threshold. The term "Baroque" itself, as an artistic period, was only formalized in Heinrich Wölfflin’s 1888 treatise Renaissance and Baroque. Its etymology is debated: Portuguese barroco ("irregular pearl") or the medieval logical term Baroco, denoting convoluted complexity. By the 16th century, "baroque" signified the ornate and extravagant.

This historical reveals art’s intrinsic momentum: when a paradigm (Renaissance classicism) peaks, rebellion (Mannerism) inevitably follows. Conceptions of "reality" shifted from universal, eternal ideals toward capturing dynamic immediacy, intense emotion, and theatrical "truth." Definitions of "beauty" expanded beyond harmonious absolutes to embrace expressiveness, tension, even conflict. Scientific rationality (anatomy, perspective), once tools for idealization, now served individual expression and visual innovation.

This prologue, charting art’s turn from classical to modern, provides the essential framework for comprehending Caravaggio: How could his "realism" (saints as peasants) coexist with overpowering "theatricality"? How did his "unadorned" naturalism pioneer the "ornate" Baroque? The answer lies in this profound metamorphosis—where the pursuit of "perfection" yielded to the expression of "dynamic reality" and "human passion."

In the next chapter, we enter Caravaggio’s world of chiaroscuro, violence, sanctity, and squalor—where Dionysian frenzy and gambler’s nerve ignited Baroque’s incendiary brilliance, forever transforming perceptions of "truth" and "art."

About Artphiloso

Hi, I’m Philo, a Chinese artist passionate about blending traditional Asian art with contemporary expressions. Through Artphiloso, my artist website, I share my journey and creations—from figurative painting and figure painting to floral oil painting and painting on landscape. You'll also find ideas for home decorating with paint and more.