In the traditional Chinese art system, “Xieyi” (写意) is a central aesthetic concept spanning painting, calligraphy, and opera. Unlike Western realism, which emphasizes faithful reproduction, Xieyi art aims to convey the spirit and inner world of objects through sparse yet expressive brushwork. The idea traces to the pre-Qin notion of “de yi wang xiang” (“grasping the meaning, forgetting the form”). It first emerged in theory in Tang dynasty via Zhang Yanyuan’s Records of Famous Painters of All Dynasties. When literati painting rose to prominence in the Song era, Xieyi became a dominant creative principle, reaching its apogee in the works of Xu Wei and Bada Shanren during the Ming–Qing periods. This historical arc clearly marks China’s shift from valuing “formal resemblance” to emphasizing “spiritual resemblance.”

The core of Xieyi lies in the fusion of Daoist and Zen Buddhist thought—especially Daoism’s “carry meaning beyond words” (de yi wang yan) and Zen’s “direct pointing to the mind.” Zhuangzi’s idea of “casting off robes to attune with creation” argues for escaping external form to seek inner freedom. Zen’s notion of sudden enlightenment underscores transcending appearances to touch the essence. Together, they mold the Xieyi impulse: rejecting mechanical replication, leaning instead on intuitive insight.

The Tang painter Zhang Zao put it succinctly: “Externally learn from nature; internally obtain the source of the heart” (wai shi zaohua, zhong de xinyuan). This aptly captures the dialectic between objective observation and subjective expression that Xieyi demands.

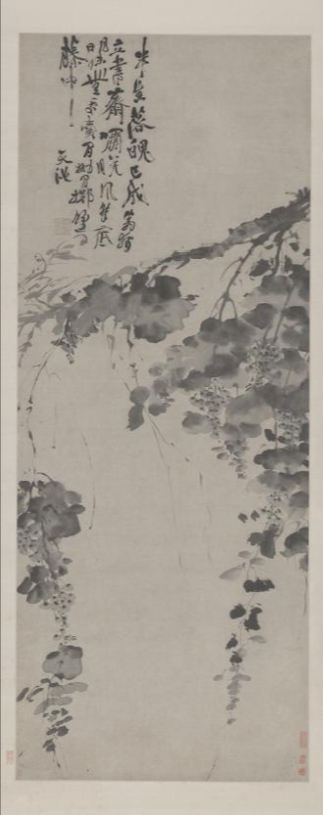

In painting, Xieyi builds its imagery via the interplay of ink dynamics (dark, light, wet, dry) and brush rhythm (fast, slow, bold, light). Liang Kai’s Immortal in Splashed Ink (Song) conjures an ethereal form via spontaneous strokes. Xu Wei’s Ink Grapes (Ming) channels frustration with vigorous ink, while Bada Shanren’s fish-and-bird works (Qing) use distortion to express solitude and moral integrity. These masterpieces confirm that Xieyi is not about copying appearances, but about using them as conduits for spiritual revelation.

The compositional philosophy of “leaving white as black” (ji bai dang hei) transforms blank space into meaningful extension, realizing the ideal: “the unpainted becomes wondrous.”

The Xieyi ethos finds its fullest form in cursive script (caoshu). Tang master Zhang Xu shattered structural constraints, converting emotional resonance into brush rhythm. In Huai Su’s Autobiography, flowing, interlaced strokes maintain legibility while achieving dynamic shifts in tempo and weight. As Sun Guoting put it in A Treatise on Calligraphy: “When emotion moves, form responds; it mirrors the essence of poetry.” Thus calligraphic Xieyi is the resonance of brush form and inner emotion. Techniques like feibai (interrupted strokes) and careful density/spacing visually trace the calligrapher’s inner journey.

In Chinese opera, Xieyi manifests through stylized movement and symbolic staging. In the Peking opera The Crossroads, actors portray a fight in darkness using only physical gestures under bright light; in the Kunqu piece Autumn River, a single oar motion evokes riverine travel. Such minimal means invite audiences to complete the imagery in their minds. The power of Xieyi lies in simplifying the complex—using archetypal gestures to spark imagination—offering a stark contrast to Western theater’s realistic sets.

In literature, Xieyi appears in the principle “construct image to exhaust meaning” (li xiang yi jin yi). Tao Yuanming’s “Plucking chrysanthemums by the eastern fence, I gaze at the southern mountains at ease” evokes serene detachment. Li Bai’s “We look at each other, neither tired—the Jingting Mountain and I” conveys aloof nobility. Su Shi’s “Clad in a rain-cloak, I let life drift freely through wind and rain” captures philosophical equanimity. These lines do not strive for meticulous scene description; instead, they capture the fleeting merger of subject and object, achieving “words end, meaning continues.” Literary Xieyi lies in creating a resonance field between imagery and emotion.

In modern times, Xieyi experiences renewal across digital art, animation, and design. The animated film Feeling from Mountain and Water merges ink aesthetics with digital technology. Architectural “emptiness design” sustains the spatial aesthetics of traditional painting; deconstructivist fashion echoes Xieyi’s expressive spontaneity. In the global art dialogue, Xieyi offers a creative philosophy that prizes spiritual resonance over mere form, enabling cross-cultural dialogue grounded in inner vitality.

Unlike Western Expressionism, which foregrounds emotional outburst, Xieyi emphasizes subtlety and poetic mood (yijing). And distinct from Abstract Art, which abandons representation entirely, Xieyi retains a visual conversation with nature’s essence. Such a stance ensures its unique place in global art and furnishes rich possibilities for intercultural exchange.

Hi, I’m Philo, a Chinese artist passionate about blending traditional Asian art with contemporary expressions. Through Artphiloso, my artist website, I share my journey and creations—from figurative painting and figure painting to floral oil painting and painting on landscape. You'll also find ideas for home decorating with paint and more.